Why Chinese artist Wu Guanzhong’s East-meets-West paintings still sell for millions

French-trained artist inspired by Picasso and Cézanne, who died in 2010 aged 90, was known for his landscapes that fuse deft Chinese strokes with Western form and colour

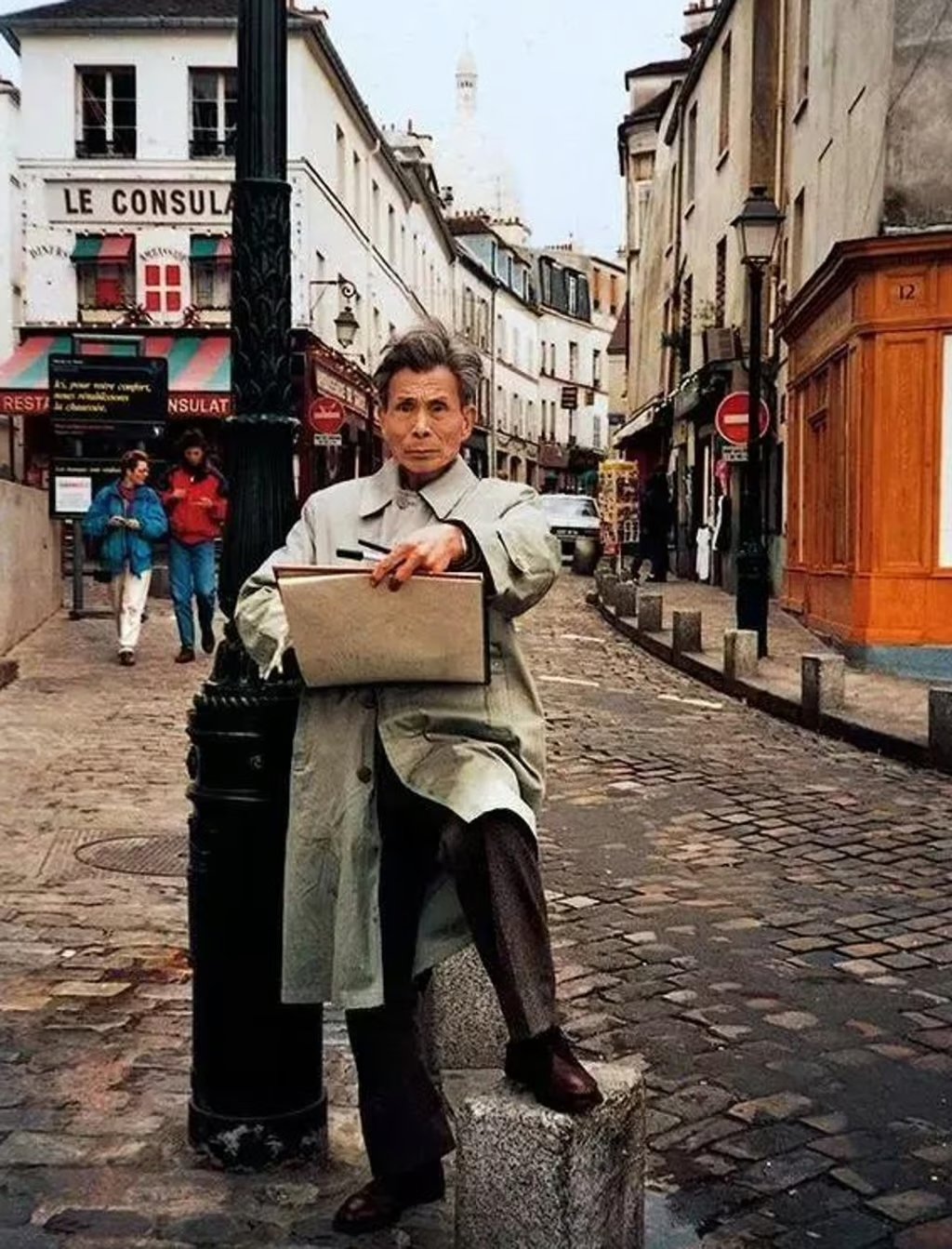

Wu Guanzhong sketches in France, where he studied art in Paris on a scholarship.

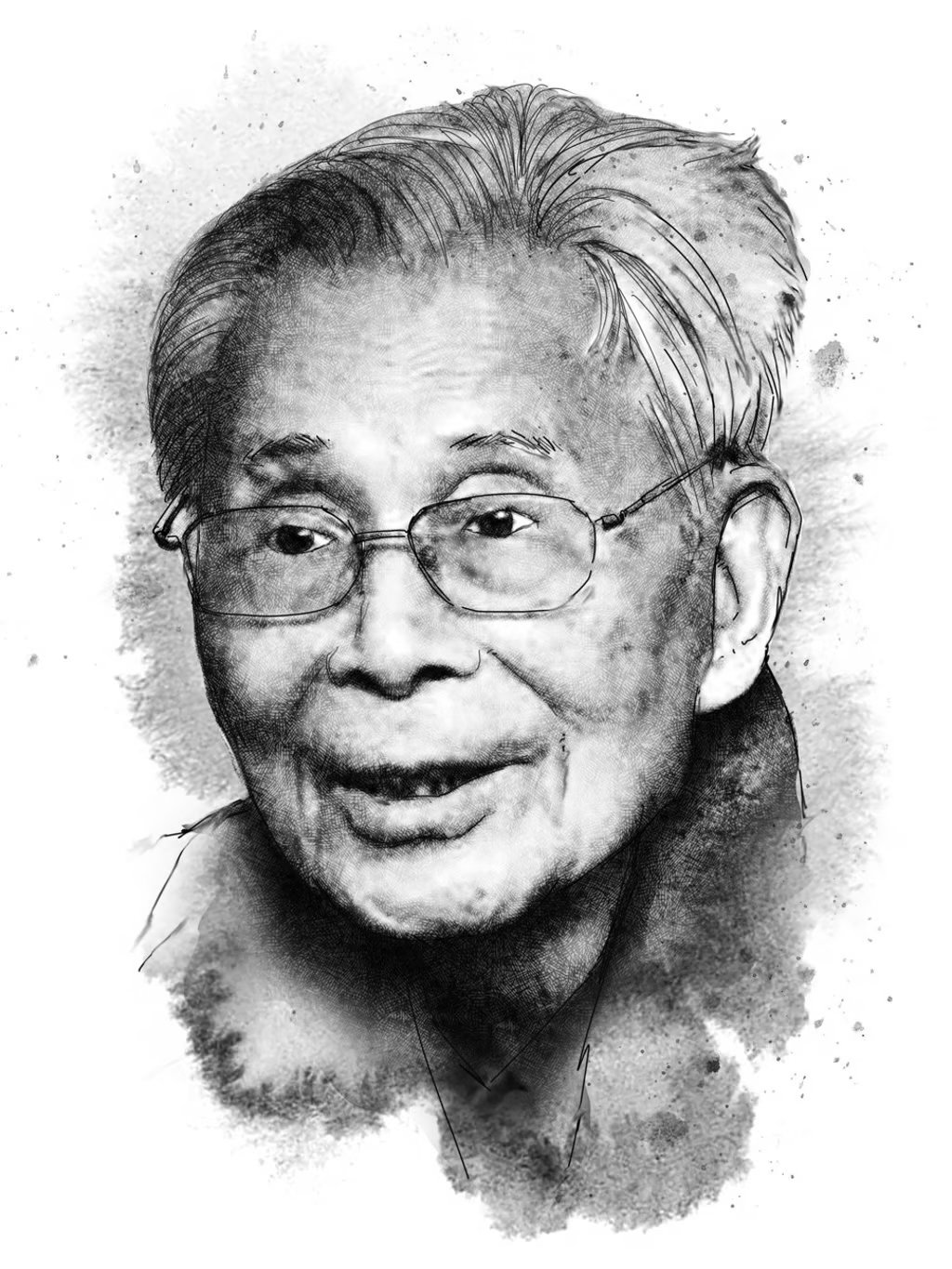

The Chinese master painter, Wu Guanzhong, who used the works of Picasso, Gauguin and Cézanne as the inspiration for his paintings fusing Eastern and Western techniques, would have celebrated his 100th birthday on August 29, 2019.

Today Wu, who died aged 90 in 2010, is regarded as one of China’s most influential and important artists of the 20th century, with some of his artworks selling for millions of dollars.

In 2010, for example, shortly before his death, his 1974 oil painting, Panoramic View of the Yangtze River, sold for US$8.4 million at auction in Beijing.

A collection of numerous water-ink works by the artist, under the theme, “Delightful Hong Kong: Important Private Collection of Wu Guanzhong from Singapore”, were included in the first Hong Kong auction of Holly’s International spring sales at the Grand Hyatt Hong Kong, in Wan Chai, on Monday.

Wu, who used the medium of ink and oil throughout a career spanning more than 60 years, had a career that is just as colourful and interesting as the many artworks he created.

In 1992, he became the first living Chinese artist to stage an exhibition at London’s British Museum, titled “Wu Guanzhong: A 20th-Century Chinese Painter”.

This was an extraordinary achievement for an artist once banned from painting for seven years during the Cultural Revolution after being denounced as a “bourgeois formalist”; he was later banished to the remote countryside to perform manual labour.

Landscapes formed a big part of Wu’s later works, but he began his artistic career studying mainly oil paintings and the human form. He worked on several nudes in the early years, only to destroy them in the 1950s, and did not return to the subject again until 1990.

Born in 1919 in Yixing, in Jiangsu province, Wu started studying art in Hangzhou before winning a scholarship to travel to the French capital, Paris, in 1947 to further his art studies at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts.

I used Eastern rhythms in the absorption of Western form and colour, like a snake swallowing an elephant. Sometimes I felt I couldn’t gulp it all down

Wu Guanzhong, Chinese artist

Wu later remarked: “I used Eastern rhythms in the absorption of Western form and colour, like a snake swallowing an elephant. Sometimes, I felt I couldn’t gulp it all down.”

His admiration for notable European painters, such as Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and Vincent van Gogh is evident in the work he produced during that time.

Wu’s paintings showcase the artist’s lively, lyrical style of semiabstract forms which skilfully integrated the traditional Chinese sense of space with the colourful charm of Western art. They are Wu’s mature works in the field of ink exploration.

Delicate Chinese brush strokes combine with Western oil painting techniques, using colour and form to create sweeping landscapes and waterscapes.

Aspects of his Chinese homeland pervade his art. Subjects include architecture, people, fauna and flora.

Today his influential body of work combines a mix of art and essays, for during his lifetime he not only published albums of his paintings but also several collections of his writings, including the essays, “The Formal Beauty of Painting” and “On Abstract Beauty”, in which he reflected on the aesthetic forms in Chinese art.

His theories kicked off a debate on modern forms in Chinese painting and his legacy continues to endure.

“Wu Guanzhong’s view of art is vividly reflected in his works and clearly seen in his writings,” says Jessica Lee, general manager of the Holly’s International’s department of modern and contemporary art.

“In the 1980s, the social and cultural environment was undergoing drastic changes. It was a turbulent time for Chinese art, when people weren’t brave enough to question the rules and dogmas.

Works by the late Chinese artist Wu Guanzhong’s paintings, including this painting, ‘An Old Tree’, often sell for huge sums at auctions around the world.

“Wu was always at the forefront and shared his insights. Some of the earliest articles in the theoretical circle that involved malpractice – arousing controversy and generating repercussions – were mostly written by him.”

After returning to China in 1950, Wu gradually introduced aspects of Western art to his students while teaching at the Central Academy of Art in Beijing.

“[During that decade] Wu focused on landscape painting in oils and watercolours and explored the “nationalisation” of oil painting [the idea of which saw Chinese art and artists providing political service to the nation in a Social Realist style, which featured heroic workers, farmers and soldiers].

“It was not until 1974 that he started to create ink paintings again, but not in the traditional style. Instead, he found his own way, by integrating Western formal structure and formal language into traditional ink paintings to create his own unique style.”

Wu, whose influence on art has been called “revolutionary”, staged an exhibition of his work at the Beijing’s Central Academy of Art and in 1991 France made him an Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, in recognition of his significant contributions to the arts.

the second time – had donated invaluable works by the artist to the museum for its permanent collection.

Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam attended a ceremony at Government House in Central, to mark the occasion, during which she presented Wu’s eldest son, Wu Keyu, with a certificate of appreciation.

Wu’s connection with Hong Kong goes back to the 1950s. After his return from Paris, he visited the former British colony and returned on numerous occasions to paint, host art exhibitions, attend academic seminars and give lectures.

The city also proved to be a source of inspiration for his sketches, from Aberdeen and Repulse Bay in the south to Central and the Mid-Levels, and across the harbour to Tsim Sha Tsui and Jordan’s Temple Street.

Wu once said: “In Hong Kong, I could see the East and the West. People can exchange their ideas in almost anything … That’s why I like Hong Kong.”

Original article published on South China Morning Post (May 31, 2019)